Eight hours with Bio 8 through Hamburg

A day on the road with a biowaste wasteworker team of Germany’s largest harbour city

5:45 a.m., Hamburg night in October. The harbor shines in the distance, and around us shine the orange vests of 1.000 employees of Hamburg’s city cleaning service, who now swarm out from the northwest depot to clear the two million metropolis on the Elbe, of litter. We wanted to know what their daily routine is like and accompany Michael Wirschke and his team on their tour.

“Moin, are you Bio 8?” Moin is the Hamburg term for „Good morning“ which is used during the whole day. The friendly man behind the wheel nods. We attach ourselves to the rear of the biowaste vehicle, which reminds of a concrete mixer with ist round collection drum. We drive through the slowly filling streets eastward toward the city center.

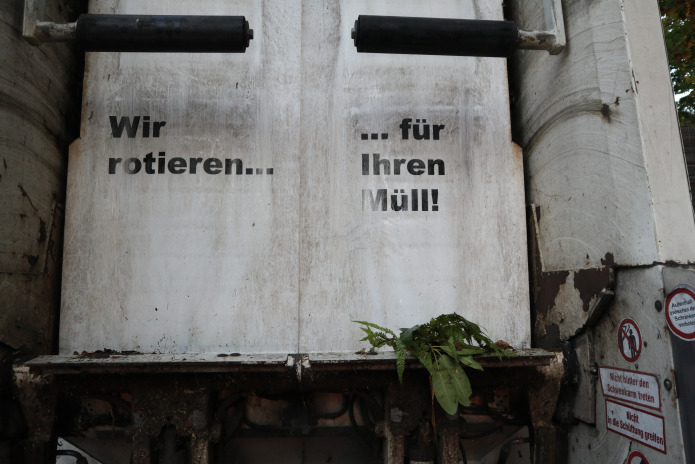

On the rear we notice the motto: “We rotate … for your waste.” During the tour we experience that this motto is literally true, with Michael, Blandine and Frank empting about 750 of the total of 150,000 organic waste bins, in which an amount of 75,000 tons of organic waste per year is collected throughout the city.

750 times up the bins – often the heavy biomass doesn’t come loose right away

After a quarter-hour drive, Michael Wirschke stops at a place where the first green bins are waiting for us. Blandine and Frank jump out of the cab, pull the 2- and 4-wheel bins to the pickup, the hulls tip upwards with a jerk, wriggle upside down in the cool morning air until all the green stuff, often heavy and entangled, comes loose, which sometimes happens only at the second attempt, then the bins are set down on the pavement and pushed back to the starting position in no time at all. So it goes on and on in close rhythm, Blandine and Frank stand on the back of the truck, climb up and down, walk parallel alongside the truck and ahead, pull bins from backyards, because only those with a red lid are brought directly to the street by the residents, and take over the role of the instructor in narrow places.

With the eye of 31 years of driving experience, you can get around any corner

When asked how he reacts, if a parking car blocks the street, Michael Wirschke just shrugs his shoulders. In fact, it’s hard to imagine an event that could upset this veteran with three decades of professional experience. “Most of the time, I back up and then pull over from the other side, which is faster than calling the police and waiting for the tow truck, becaus you easily loose 2 hours. You can do that, but I prefer to keep moving.”

With the eye of 31 years of driving experience, you can get around any corner

When asked how he reacts, if a parking car blocks the street, Michael Wirschke just shrugs his shoulders. In fact, it’s hard to imagine an event that could upset this veteran with three decades of professional experience. “Most of the time, I back up and then pull over from the other side, which is faster than calling the police and waiting for the tow truck, becaus you easily loose 2 hours. You can do that, but I prefer to keep moving.”

Bio 8 travels up to 78 roads per day and collects an average of 13 tons of organic waste

While Michael talks about security, we are amazed about the pensum, that Blandine and Frank reel off. We don’t have an odometer, but they certainly make quite a few kilometres. During the break at a traffic-calmed corner, Blandine, who has only been on the team for a few months, tells us that her feet hurt quite a bit in the evenings at first. Now she got used to it. After all, she is out in the fresh air all day, which is something that not every working person can claim. Frank agrees. He is originally from the bulky aste team, but due to a staff shortage temporarily helps out and finds his way around the organic business right away.

How do we know where the containers are? – Communication is the key

We notice that Team Bio 8 picks up a lot of bins from the lots, opening locked gates with skill and moving unerringly to bin areas. “Actually, it takes about half a year to know which way the wind is blowing“ says Michael, „but Blandine and Frank are pretty fit after a short time. If they’re unsure, I point out where the next bins are via the rearview mirror, and the two of them exchange on the back of the truck.”

The nice thing is that you get to know the city and the people

It seems to work well with communication. In any case, we make a hook at one road after the other. In the meantime it is noon and today’s tour is coming to an end. The shift lasts from 6:00 a.m. to 2:06 p.m, the truck is scheduled to return to the northwest depot at about 1:00 p.m. There’s still a bit of time to chat. “By now, we know many residents, at least those who push their bin with the red lid to the street and are already waiting when we come to bring it back in. By the way, Vitali Klitschko lives back there. He’s got a red lid, too.” Michael radiates a pleasant contentment; he has been driving garbage trucks for 31 years and previously worked as a stone setter for 15 years, which was a really tough job in his eyes. Now he is crusing day after day high up in his cockpit above the streets of Hamburg, turning today’s waste into tomorrow’s resource.

Tschüss is what they say in Hamburg

We turn off for the last time and say goodbye to our Bio 8 team with a Hamburgian “Tschüss” and a big smile. It was a pleasure to accompany Michael Wirschke, Blandine Föhse and Frank Schäfer on their tour through Hamburg’s west.

PS: What actually happens to approx. 75,000 t of Hamburg’s biowaste per year?

Biogas is produced from the biowaste, which is used to supply electricity to households in Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein. Subsequently, the waste is turned into high-quality compost, which is highly valued as a fertilizer. The complete recycling process takes place at the biogas and composting plant in Bützberg.

After the garbage trucks have loaded the biowaste from Hamburg households, they drive to the biowerk and unload the collected biowaste there in a closed receiving hall with a venting system. The unloaded organic waste is then transported to a conveyor belt system with the help of a large wheel loader.

There, screening systems free the organic material from foreign matter, such as plastic films or metals. In addition, a screw mill crushes the raw material until the individual pieces are smaller than 8 cm.

Gas-tight chambers, so-called fermenters, of the biogas plant are filled with the processed material.

(A digester is about 24 meters long, 5 meters wide and 4.5 meters high, so that up to four garbage trucks would find room in it).

In a total of 21 digesters, billions of methane-producing bacteria decompose the processed organic material for three weeks. This takes place in the absence of air and at a constant 38°C.

The biogas produced consists of half methane and half carbon dioxide, whereby only as much carbon dioxide is produced as the plants have previously extracted from the atmosphere in order to build up the organic substance required for plant growth. In the fermenters of the biogas plant, this carbon taken from the atmosphere is broken down into methane, among other things. The biologically produced biomethane therefore does not pollute the atmosphere with additional amounts of climate-damaging carbon dioxide when burned, unlike fossil methane in normal natural gas. The annual production of the SRH biogas plant can save about 7,250 tons of carbon dioxide annually. (To remove this amount of carbon dioxide from the air, 4,000 spruce trees would have to live to be 100 years old).

The biogas mixture is captured by three storage tanks and then purified in the adjacent upgrading plant to achieve natural gas quality.

Under full load, the plant manages to feed up to 350 cubic meters of biomethane per hour into the natural gas grid of Schleswig-Holstein AG, which in turn supplies households in Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg with electricity. The energy generated is equivalent to the electricity needs of more than 11,000 two-person households.

The remaining digestate is mixed with some raw biowaste to form an optimal starting position for the subsequent rotting process. Five conveyor belts transport the biowaste into the 22-meter-wide and 125-meter-long enclosed rotting hall, where it is piled up into compost heaps. The composting process takes place on ten well-ventilated rotting fields.

The heart of the composting plant is “Wendelin,” a powerful machine with a three-meter-high paddle wheel. It shifts the windrows twice a week. Wendelin also ensures that the material is watered as needed during the maturing process. Automatic aeration, which exchanges the air in the windrows up to six times an hour, ensures a steady supply of oxygen to the rotting material.

(Unlike their counterparts in the digesters, the compost microbes need oxygen to do their work).

This creates all the conditions for optimal decomposition of the organic matter. After four to five weeks, composting is complete.

The activity of billions of small bacteria and fungi generates temperatures of over 60 degrees. This guarantees complete hygienization of the product. Even undesirable wild weed seeds can no longer sprout when the compost is used in the garden or on the field.

After the rotting process, Wendelin transports the finished compost out of the hall. Sifted and packed in bags or as loose material, as required, the organic compound fertilizer of the highest quality (certified by the RAL seal of quality) is then ready for customers.

SULO – Creating solutions to turn today’s waste into tomorrow’s resource

Herford, November 2021

Text: Jörg Rosenstengel

Photography: Imke Willmann